So Through The Singing Land He Passed

An exhibition curated by Sabina Mac Mahon in response to the work of Maimie Campbell • Michael-John Cervi, Conor Dowling, Caoimhseach Ní Lamhna, Emma O’Brien and Sophie Prendergast

Made in collaboration with the Centre for the Study of Irish Art at the National Gallery of Ireland and Dr Lisa Godson, historian of design and visual culture.

The Easter Rising is an event as mythical as it was real.

– Róisín Higgins, 2013, p.5

In April 1966, under the directorship of James White, the National Gallery of Ireland presented Cuimhneachán 1916, an exhibition of “Pictures, Portraits and Pieces of Sculpture relating to Irish History” that formed part of the State’s official golden jubilee programme of public ceremonies and events celebrating the fiftieth anniversary of the Easter Rising. Largely comprising of portraits of participants in the Rising and described by one art critic as being ‘naturally enough, a historical rather than an artistic affair’[1], the exhibition was an ‘unqualified success’ and attracted almost 60,000 visitors to the gallery[2].

Taking Cuimhneachán 1916 as a starting point for her exhibition at The LAB, curator Sabina Mac Mahon spent time studying archival material relating to the 1966 commemorative exhibition at the National Gallery’s Centre for the Study of Irish Art (CSIA). Among the notes on works borrowed for the exhibition and general administrative paperwork contained within the three files connected with the show, she came across a letter from a little-known Northern Irish artist named Maimie Campbell (1905-1997) offering to loan the National Gallery a small painting of The Death of Cúchulainn that she had made almost forty years before for inclusion in Cuimhneachán 1916. Coincidentally, in late 2013 Mac Mahon had begun researching the work of members of the pioneering South Down Society of Modern Art, active in Ulster in the mid-1920s. Maimie Campbell was a prominent member of the group and her painting of Cúchulainn (which was not accepted by the National Gallery for its Easter Rising golden jubilee exhibition of 1966) had been included in the two-part exhibition of the group’s work curated by Mac Mahon in Belfast in 2015.

Intrigued by this second chance encounter with Campbell’s work, Sabina Mac Mahon decided to invite five emerging artists to make new work in response to Maimie Campbell’s 1929 painting of The Death of Cúchulainn. The resulting exhibition, So Through The Singing Land He Passed, comprises photography, performance, video, painting, drawing and sculpture/installation that interrogates and reinterprets Campbell’s endearingly derivative but highly idiosyncratic take on avant-garde modernism, as well as her preoccupation with Cúchulainn, hero of the Ulster Cycle of mythological tales. Closer in spirit to the ‘truth’ of 1966[3] than that of 1916, So Through The Singing Land He Passed negotiates a commemorative tradition now synonymous with the cultural nationalism of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century: the discrete, and almost exclusively Irish, practice of looking back to an imagined past of allegory and myth in order to memorialise, through symbol and metaphor, real people and events. A small display of original paintings by Maimie Campbell and archival material relating to her life and work, as well as the Cuimhneachán 1916 exhibition at the National Gallery of Ireland, complete the show, which ultimately exists as an ephemeral commemorative gesture that serves to highlight the multiple frailties and failings inherent in any attempt to commemorate by drawing legitimacy from the past, whether real or imagined.

In his work The Exact Spot Where Patrick Pearse Surrendered: Parts 1, 2 and 3, photographer Conor Dowling documents the three sites on Parnell Street (then Great Britain Street) posited by various conflicting sources as the place depicted in the well-known “surrender” photograph of Pádraig Pearse and General Lowe, taken at 3.30pm on 29 April 1916, the day the Provisional Government of the Irish Republic effected its unconditional surrender. It contrasts with two smaller photographic works that bear witness to two places in Louth that Cúchulainn is traditionally associated with. These locations are echoed in Sophie Prendergast’s elegant sculptural pieces The Plain of Muirthemne (located in the north-east of present-day Leinster) and Clochafarmore (the stone pillar in Rathiddy, near Ardee, which Cúchulainn is said to have tied himself to during his final battle so he would die upright, facing his enemies). She also includes a rare representational work, The Morrígan, phantom-queen harbinger of death, displayed alongside a small concrete sculpture entitled Leath de Dhá Chich na Morrigna.

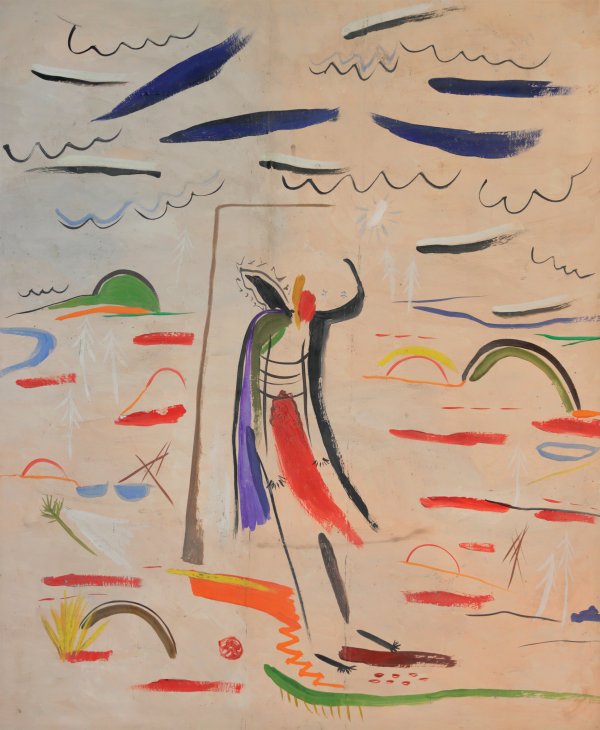

Themes of life and death recur throughout the exhibition and are highlighted in video and performance artist Michael-John Cervi’s The Living Death of Cúchulainn. Filmed in Dublin, the looped video shows a ‘living sculpture’ street performer repeatedly enacting Cúchulainn’s death in the guise of Oliver Sheppard’s iconic sculpture, The Death of Cúchulainn (1911-12), which was unveiled by Éamon de Valera as the official memorial to the 1916 Rising at the General Post Office in 1935. Emma O’Brien chooses to depict the legendary hero in happier times, posing with his hereditary sword, crimson throwing shield and gáe bolga in a meticulously rendered larger than life-size drawing of the frontispiece illustration in L.M. McCraith’s 1924 text The Romance of Irish Heroes (an original edition of which was owned by Maimie Campbell) from which the exhibition takes its name. His exuberant energy is also captured in Wonder-Hero, Hero-Light, a series of resolutely abstract paintings by Caoimhseach Ní Lamhna that attempt to capture the essence of fleeting impressions of events in Cúchulainn’s life that find parallels with real-life historical events associated with the Easter Rising while simultaneously adhering to their own pictorial logic.

____

[1] Fallon, Brian. (1966) ‘1916 History in National Gallery’, The Irish Times, 8 April, p.7.

[2] White, James. (1966) Form letter sent to individuals and organisations that loaned work to the National

Gallery for inclusion in the exhibition. Cuimhneachán 1916 archive papers at the CSIA.

[3] Higgins, Róisín (2013) Transforming 1916: Meaning, Memory and the Fiftieth Anniversary of the Easter

Rising. Cork University Press, p.27.

Monday to Saturday 10am – 6pm. We are currently closed on Sundays.