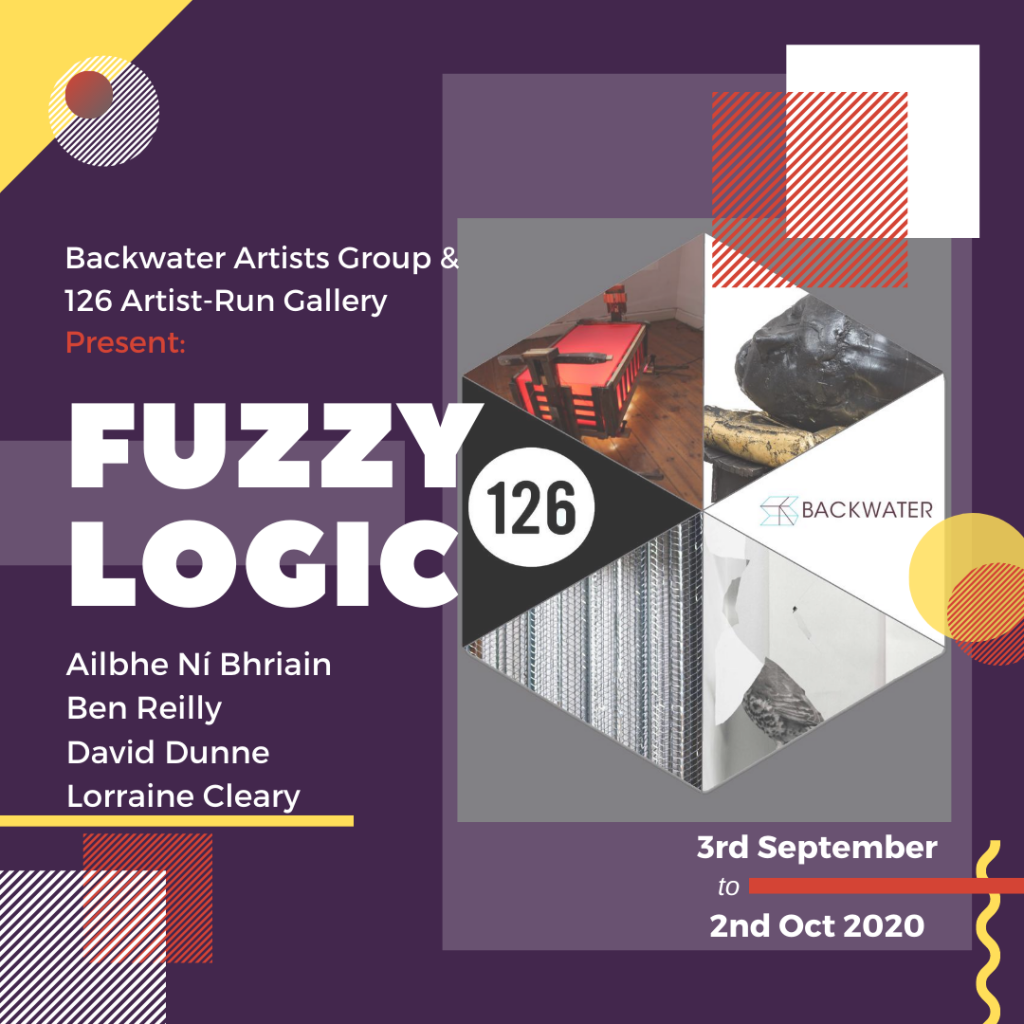

Fuzzy Logic

Curated by Simon Fennessy Corcoran (126 Artist-Run Gallery and Studios, Galway) • In association with Backwater 30 year anniversary

Viewing by appointment only (021 4961002 / admin@backwaterartists.ie). Email or phone ahead OR just phone upon arrival.

The exhibition is a kaleidoscope of approaches to the entropy of uncertainty and fuzzy logic. Featuring 126 artists Lorraine Cleary, David Dunne and Backwater studio members Ailbhe Ní Bhriain and Ben Reilly. A second, larger iteration of the exhibition will be held subsequently at G126, Galway.

“Uncertainty is a term used in subtly different ways in several fields, including philosophy, statistics, economics, finance, insurance, psychology, sociology, engineering, and information science. It applies to predictions of future events, physical measurements already made, or to the unknown. It may also examine how we navigate the world, from our individual or small clustered points of view. We look at everything from different vantage points and interact with the world, with art and with each other.

The philosophical problematics of uncertainty are often tied to several conditions: Fallibility of human beings; the limit of knowability of or accessibility to the past and future; contingency and spontaneity of human decisions and actions that affect social phenomena. Uncertainty, thus, has both ontological and epistemological elements that appear in various ways in social, historical, cultural phenomena and our understanding of these and other can be discussed in reference to belief and faith. Below I outline how uncertainty permeates across human existence and effect the world around us.

Artist William Kentridge plays with the idea of uncertainty in his work with a self-awareness of this as an important polemical and political element to art. In having a critique of the uncertain, contradiction and ambiguity, Kentridge uses this as the essential lifeblood of art. In experimentation and creative problem-solving. Uncertainty in meaning and construction is not just mistakes at the edge of understanding but the way in which understanding can be constructed, making us aware of constructing meaning rather than just receiving information. He sees these as all natural to art and all are models of how understanding the world could be. His work tackles the ambiguity of society, from apartheid tensions to human experiences of uncertainty. This was the staging ground from which grew the curatorial theme.

Uncertainty is inherent in life and permeates all aspects of the world. Austrian physicist, Erwin Schrödinger used uncertainty to postulate some of the most challenging scientific theories known to man, one of the most impactful of which, and which is still debated today by contemporary scientists, is the “Schrödinger’s cat” thought-experiment, devised by Schrödinger in 1935. The scenario presents a cat that may be considered simultaneously both alive and dead, a state known as a quantum superposition, as a result of being linked to a random event that may or may not occur. According to Schrödinger, the Copenhagen interpretation implies that the cat remains both alive and dead until the state has been observed. While the box is closed the uncertainty develops into a paradox of two states of simultaneous existence until viewed either by technology or biologically i.e. the human eyes.

Philosophy as with science tries to establish immovable valid principles with certainty. Be it agnosticism or scepticism, it tries to establish “unknowability” or uncertainty of knowledge or a limit of cognitive capabilities of human being as the valid principle. If, on the contrary, scepticism is sceptical about its position, it is self-defeating, and it cannot establish its position. Thus, a quest for certain knowledge or valid knowledge exists at the root of philosophical inquiries. Conversely, philosophical inquiries begin with the fundamental insight or conviction that human being is fallible, and all knowledge must always have some element of uncertainty. Philosophers, thus, inquired after a way to get to the valid philosophical claims. In religious philosophy, uncertainty of knowledge is rooted in the insight that human being is fallible. Religious philosophers present faith, belief, and revelation to overcome the limitation of fallibility and reach valid knowledge and certainty in faith.

Philosophers also tried to find some methods, such as phenomenology, linguistic analysis, or certain areas such as language by which we can gain certain knowledge. Philosophical methodologies and epistemological perspectives have been presented as ways to gain knowledge. In some views, the question of uncertainty also arises from the temporal limits of existence. Both events in the past and those in the future are not accessible to us; the past is always reconstructed by some hermeneutic schema. The reconstructed past is always selective, partial, and interpretive; hence it essentially retains some degree of uncertainty. The future is also uncertain for human action and natural phenomena is contingent and spontaneous. Human beings exist with a recognised possibility of death; uncertainty and anxiety are thus essential to human existence.

Finally, the idea of fuzzy logic and uncertainty pertains to how we morally negotiate the world we inhabit, a prime example can be seen with Michael J. Zimmerman’s book, “Living with Uncertainty: The Moral Significance of Ignorance” which offers a conceptual analysis of the moral ‘ought’ that focuses on moral decision-making under uncertainty. The central case of the book concerns a doctor who must choose among three treatments for a minor ailment, evidence suggests that drug B will partially cure the patient, that one of either drug A or C would cure them completely, however, the other drug would kill them. Accepting the intuition that the doctor ought to choose drug B, Zimmerman argues that moral obligation consists in performing the action that is ‘prospectively best,’ that is ‘that which, from the moral point of view, it is most reasonable for the agent to choose’ given the evidence available.

According to the Objective View, a person ought to choose what is, in fact, the best option. The doctor ought to give the patient whichever drug will cure him. The fact that the doctor cannot know which will cure and which will kill creates a situation of fuzzy logic where both sides can argue for the moral right. In this decision multiple points of view can exists, each believing they hold the truest moral opinion.

What is the right decision? Is this not simply altered by our individual perspective and the information available to each of us. But as humans, who are inherently fallible, are our information systems not imprecise, incomplete and unreliable? How do we ever know what is right with this uncertainty which objectively must always exist within existing human information systems and the perspectives which exist.” Simon Fennessy Corcoran

Wandesford Quay, Cork