Fragments, Metaphors, Smithereens

A three-person exhibition of new prints

The exhibition explores a number of aspects of Irish History. The Easter Rising of 1916 in the work of Merijean Morrissey. References to the history of the Irish College, Centre Cultural Irlandais in the work of Geraldine O’Reilly, based on her research whilst artist in residence at the college, and the Curragh Internment Camp in the work of Margo Mc Nulty where her great uncle was interred.

______

Tintown

The history of the Curragh, in Co Kildare, is permeated by violence. A large, open, sandy-soiled expanse of flatland, a landscape of modest beauty, it has been since the mid-nineteenth century the home of a sizeable military barracks and also, for many years, of a large internment camp. Francis Bacon, who was born and spent his early childhood nearby, at Cannycourt, recalled the Curragh as a landscape of theatrical brutality: a parading ground for military rehearsals before the First World War, and afterwards, during the War of Independence, site of a grimmer, more all-pervasive sense of threat. (It is a landscape which seems to have informed the violence of the painters world-view, his sense of the body as fragile flesh.) During the Second World War, as well as interning Axis or Allied personnel detected in Ireland, a separate division of the camp was used to hold members of the IRA. While foreign army personnel were allowed certain privileges given a clothing allowance, allowed to garden and attend religious services the Irish internees were treated much more harshly. The camp came to be known with the same unsettlingly gently understatement as the Emergency or the Troubles as Tintown.

When I meet with Margo McNulty to talk about her work, at the Graphic Studios Workshop on the North Circular Road, she lays out a series of photo-etchings on a table-top: images of bare uncomforting landscapes. She tells me about her grand-uncle, who was interned as a republican at the Curragh camp during the war. He was badly mistreated, she tells me, as were all the Irish prisoners. (Historians corroborate this story. Irish prisoners in Tintown were subjected to shameful levels of violence and psychological strain. Upon release, many found themselves unable to adapt to life in the outside world.) He died shortly after being released, as a result of his treatment. McNulty does not know all the specifics. Her grand uncle’s experience in the camp remains something of an unspoken topic. And it is this unspoken quality that comes across in the images of empty, overgrown fields, mute trenches, and yielding mud, on this now-derelict strip of the Curragh.

Some of Those that Came Before

Similar qualities of emptiness and aftermath can be identified in Geraldine O’Reilly’s sparse, delicate, composite prints. The work being shown at the Graphic Studio Gallery emerged out of a residency at the Centre Culturel Irlandais previously the Irish College in Paris in 2013. The College dates from the seventeenth century, one of a number of such colleges around Europe where catholic seminarians, debarred from doing so in Ireland, could train. As such it was, for centuries, home to a community of devout religious emigrants; a scholarly centre for the dispossessed. O’Reilly talks to me about the history of the building, previously the College Des Lombards, which was occupied by the Irish College from 1677. In 2002, after a period when the building was occupied by the Polish Seminary, the building was completely restored, with funds provided by the Irish Government, and reopened as the CCI.

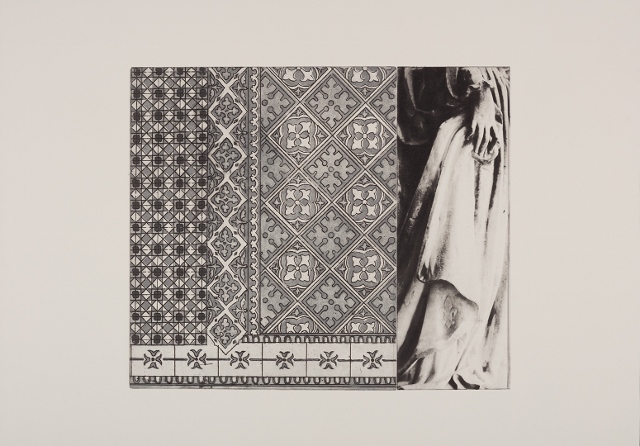

While resident there, O’Reilly became interested in the buildings prior occupants. She thought about the seminarians, far from home, receiving hand-stitched votive objects in the post, tiny sacred hearts, or pillows the size of tortellini, inscribed with devotional messages, some of which inspired the three dimensional prints in the Gallery. She thought of all those before her who had paced the ornate halls, the intricately tiled floors: the great and good like Thomas Addis Emmet and Daniel O’Connell, but also the unknown, the forgotten. The patterns of these floor tiles resurface in the series of O’Reillys works in which different images have been stacked next to each other, like books on a shelf, or (looked at another way) like the geological strata of a land formation. The floor tiles are stacked against photo-etchings depicting details a hand, a fold of fabric from the statues of the nearby Luxembourg Gardens, those idealised female forms lining the ornamental walkways along which residents of the College would also have strolled. O’Reilly juxtaposes different print techniques in each work, presenting in startling ways the quiet histories of this emigrant religious community. This is a continuation of her long-held interest, as an artist, in the experiences of Irish emigration. It is also a presentation of concretised, stratified history, reduced almost to abstraction, and imbued, hauntingly, with a sense of the pasts profound unknowability.

Easter Widows

Merijean Morrissey also generates a kind of abstraction from her historical sources. In a series of striking etchings, depicting women in the opulent veiled hats favoured in early twentieth-century Ireland, she creates a procession of visual analogies. In one, the veiled face, and the complex pictorial arrangement of the hat, is set against the tracery of a spiral staircase in Kilmainham Gaol. In another, the splendidly arraigned head is juxtaposed by a grid-like, almost architectural drawing of the Asgard, the ship which, led by Erskine and Molly Childers, brought German guns to Howth in the lead up to 1916. There is a commentary here, certainly, about the combination of violence and lavishness which characterised the Ireland of the Rising. But there is also an interesting visual effect, a compositional device which reduces the human element of these etchings Morrissey’s historical subjects to sets of geometric coordinates. The veiled hats of the Easter Widows become engineered forms, determined by forces other than fashion or taste. For Morrisey, history seems to have something of a ruthless nature. It has the inevitability, the inescapability, of gravity.

Elsewhere, a chandelier lies, concertinaed, on a drawing room floor, further evidence of this same unrelenting force. It is a striking image of the frailty of the future (the bright republic) dreamed of by the participants of the Rising. Morrissey, who was born into an American family of the diaspora, makes use of a combination of print technologies layered photo etchings and digital prints to generate a curiously uncanny effect, combining digitally precise abstraction with historical allegory.

The result is a series of visual meditations on the very nature of historical force. Morrisseys work for the Graphic Studio Gallery is distinguished by a sense of detached scrutiny, a clear-eyed focus on the trappings and limitations of luxury. It is also, like O’Reilly’s and McNulty’s work, an investigation of the past. All three artists are interested in uncovering repressed or untold histories, histories of violence and revolution, but also domestic histories, histories of thought. Each of the artists work is, in its own way, carefully layered, delicately peeling back some specific historical skin tentatively, aware of the danger, aware of the gulf but persisting nonetheless in this communal effort of recovery and retrieval.

An essay by Nathan O’Donnell, Editor Paper Visual Art Journal

Temple Bar, Dublin 2

Monday 10:00 - 17:30

Tuesday 10:00 - 17:30

Wednesday 10:00 - 17:30

Thursday 10:00 - 17:30

Friday 10:00 - 17:30

Saturday 11:00 - 17:00